Council of Heads of Australasian Herbaria

Australian National Herbarium

Biographical Notes

|

Council of Heads of Australasian Herbaria |

Ducker, Sophie Charlotte (1909 - 2004)

Ducker, Sophie Charlotte (1909 - 2004) Sophie Charlotte Ducker (née von Klemperer) was born in Berlin in 1909. Died in Melbourne, Australia, 20 May 2004.

From an early age Sophie was interested in plants, and hoped to become a botanist after studying at Geneva and Stuttgart universities. This plan, however, was interrupted by the lead up to the Second World War, which forced Sophie and her family to leave Germany. They settled in Australia, and in 1944 she was able to resume her botanical career when she became a research assistant to the pioneering mycologist, Ethel McLennan, at the University of Melbourne. Sophie remained in the School of Botany for thirty years, completing a BSc and MSc, while at the same time demonstrating, teaching, supervising students, and establishing courses in phycology. She nominally retired in 1974 as a Reader, but continued to lecture, give papers at international conferences, and to undertake scientific research with colleagues. In 1978 she was awarded a DSc, in recognition of her published work, in 1993 an LLD, in 1996 the ANZAAS Mueller Medal, and in 1997 an AM. Sophie died on 20 May 2004 at the age of 95.

At a function honouring women scientists held in Canberra in 1999, Sophie said of her career that it had three distinct phases: the mycological, the marine, and the history of botany (Ducker 1999a). Her contribution to the first and earliest of these, the mycological, will be assessed by Tom May in a forthcoming issue of the Australasian Mycologist. The second phase, the marine, was dealt with, in part, in an issue of Phycologia on the occasion of Sophie’s seventy-fifth birthday in 1984, although she continued publishing in this area up to 1991. It is to be hoped that an assessment of her entire contribution to research on algae and seagrasses, which were also her greatest passion, will be published in the future. The third phase of her career, the history of botany, is dealt with in this article. Although the most recent of her research interests, it has ended up being the one on which she worked actively for the longest time, and, as can be seen from her bibliography, was also the most productive.

Like many botanists, Sophie Ducker became interested in the history of her discipline through consulting old botanical books and specimens. As she wrote in the introduction to the collection of papers for which she was awarded her DSc in 1978: ‘The Rules of the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature made it necessary for me to elucidate the historical background of some of the early collections of marine biological material from Australia and the history of the collectors.’ This meant that many of her scientific papers had a historical dimension, but she also produced 50 works (see bibliography) in which the history of botany was her main focus. In many of these she broke new ground, bringing to light previously overlooked materials and offering succinct and intelligent insights on their significance in her favourite subject of phycology, as well as non-English language contributions to Australian botany more generally, pollination, garden history and botanical illustration.

Sophie’s first historical paper was an entry for the Australian Dictionary of Biography in 1972 on the nineteenth century Irish botanist and algae specialist William Harvey (1811-66). His life and work was to prove an enduring interest for her, and she published another six accounts of it. The most substantial of these was The Contented Botanist, in 1988, which reproduced letters about Harvey’s journey to Australia and the Pacific between 1853 and 1856. Although a selection of these letters had already been published in 1869, they were done so in a bowdlerised form, and Sophie searched for two decades before finding the originals at Harvard University in 1985. She transcribed them from scratch for The Contented Botanist and added numerous biographical and other interpretative notes, that were useful for phycologists, and, as she wrote in the Preface (p. xi), for ‘those who have an interest in academic life in Victorian Ireland and England and like to follow a gentleman traveller on a journey to Australia and the Pacific.’

While Sophie regarded Harvey as the single most important contributor to phycology in colonial Australia, she was aware that his efforts built on, and were supplemented by, other overseas-based collectors and botanists. In papers in 1979, 1981 and 1990, she considered the work of the French, Germans, and Austrians respectively, whose publications she tracked down and read in their original editions. As she conducted her research she realised that non-English speaking collectors and botanists had hitherto been under-appreciated in the history Australian botany. Moreover, in phycology, in particular, she established that Australian specimens collected by continental Europeans were vital in illuminating the relationships between different groups of algae, and between plants and animals on a world scale. Sophie particularly enjoyed her research on the French, who she found franker than other nationals in their records, and whose delight in what they discovered echoed her own feelings on first encountering the Australian landscape.

As well as foreigners, Sophie also wrote about the careers of Australian-based collectors and botanists. She appreciated the difficulties that they faced in analyzing the local flora, and that their publications marked the beginnings of Australian science. In 1981, she wrote the introduction to a facsimile edition of Samuel Hannaford’s Sea and River-side Rambles in Victoria, which was first issued in 1860. She also contributed biographical entries on several Australian-based individuals, and general surveys of their careers to a number of reference works including the Australian Dictionary of Biography (see bibliography). The most recent of the surveys, ‘A brief history of systematic phycology in Australia’, which she co-authored with Roberta Cowan, will appear in the first volume of the Algae of Australia series in 2005. This will be the most substantial paper on this subject, covering a three hundred year span from William Dampier’s voyage to Western Australia in 1699, to 2003, and includes references to Sophie’s career.

Most of Sophie’s scientific work was on algae, but after her official retirement in 1974, she collaborated with Professor Bruce Knox, also of the University of Melbourne, on a number of papers on pollination, especially of sea-grasses. This led her into a new topic of historical enquiry namely that of structural botany. Three papers resulted. In the first she and Knox traced ‘The Australian history of the genus Acacia Miller and its pollen’ noting how quickly the famous Australian botanist Ferdinand von Mueller (1825-1896) adopted polyads as a diagnostic feature in Australian acacias. In two papers in 1985 and 1986, she and Knox also reviewed the ‘nineteenth century history of the discovery of pollen structure and function in flowering plants, with special reference to aquatic forms.’ These papers all exhibited Sophie’s characteristic skills in clarity of expression, use of tables, and attention to detail. Later she considered writing a more substantial work on the history of pollen and fertilisation, but unfortunately this did not eventuate.

As she moved further into retirement, Sophie branched out of the history of scientific botany into the related field of garden history. In 1984, she published an article on the ‘Austrian Gentleman Gardener’, Karl von Hügel (1794-1870) who visited Australia between 1833 and 1837. At the same time she started translating his diary which is owned by the Mitchell Library in Sydney, but this work was eventually finished and published by Dymphna Clark. Sophie also wrote papers on the history of the system garden at the University of Melbourne, and a convict, James Fleming, who she claimed was the first gardener on the Yarra River in Victoria. In later years she considered publishing a book on the garden of Empress Josephine (wife of Napoleon) at Malmaison in France, but unfortunately this also did not eventuate. As well as writing about historic gardens, Sophie’s interest in this subject found expression in her own exquisite garden in which each plant seemed to have its own story, and she was an active member of the Australian Garden History Society.

Another historical subject that Sophie took up late in her retirement was botanical illustration. In 1992, she contributed entries on the art-work of Harvey and French artist Charles-Alexandre Lesueur (1778-1846) to Joan Kerr’s The Dictionary of Australian Artists. Three years later Kerr published another reference work Heritage: The National Women’s Art Book to which Sophie contributed articles on Pauline de Courcelles Knip (1781-1851), a French illustrator of Australian birds, and Ethel McLennan (1891-1983), Sophie’s first employer at the University of Melbourne, who taught her how to use a camera lucida to make microscopic drawings of plant and fungal structures. In 1999, Sophie also published an article on the ‘Botanical history of the floral emblems of Australia’ which she illustrated using the collections of the Baillieu Library, and in 2001, an illustrated booklet called The Story of Gum Leaf Painting which was associated with an exhibition at the University of Melbourne.

Although she regarded herself as an a ‘not very fashionable’ historian (Ducker 1999a), Sophie was influenced by trends in scholarship. In particular the rise of interest in women’s history in the 1980s led her to reflect on the life and work of Ethel McLennon, her mentor at the University of Melbourne. Sophie said of ‘Dr Mac’ that she was ‘a tower of strength to women students’ (Ducker 1988a), and no one would have known this better than Sophie herself. Sophie was also aware that her own career was an inspiration to other women and left a substantial collection of her own records at the University of Melbourne Archives, which I intend to utilise in a full-length biography. Her willingness to acknowledge issues of gender, nationality and family in shaping a career set her apart from many of her generation who wanted to believe in academia as a meritocracy. In so doing, however, she always remained positive about what has been, and what can be achieved by women in their chosen fields of endeavour.

Sophie’s contributions to history were recognized, in part, in her post-retirement honours. Nevertheless, she was reluctant to see these as heralding the end of her working life. In her nineties she continued to devise new historical projects that she would surely have pursued if not for failing health. She did manage, however, to keep up-to-date with the work of colleagues in the history of Australian botany, buying their books for her library, and reading every word before reviewing a series of them in Historical Records of Australian Science (see bibliography). She also gave her support and encouragement freely to younger historians, especially on the Mueller project at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Melbourne which is in the process of publishing this botanist’s surviving correspondence, and on a project to publish the history of the School of Botany at the University of Melbourne. It was a great consolation to her in her final years to see others follow in her footsteps in the history of botany, and for this subject to gain in sophistication and appreciation.

Source: ASBS Newsletter,

No.120, September 2004. writen by Sara Maroske, Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne

Portrait Photo: 2003 Melb. Uni. Media Unit, No.2003.0003.00124

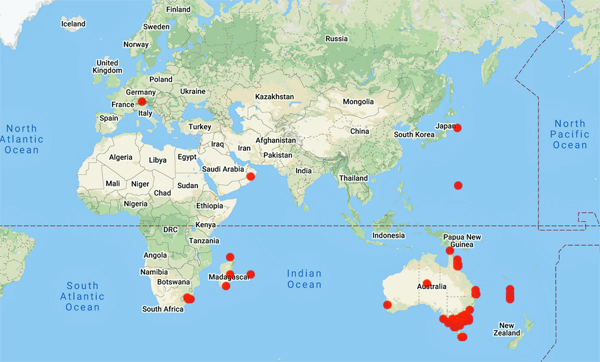

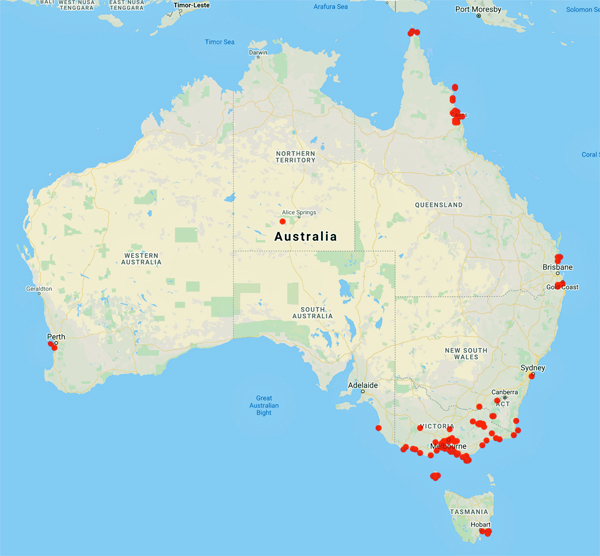

Data from 1,261 specimens