Council of Heads of Australasian Herbaria

Australian National Herbarium

Biographical Notes

|

Council of Heads of Australasian Herbaria |

OBITUARIES

Jean Galbraith

Jean GalbraithJean Galbraith, a member of that proud sisterhood which embraced the twin crafts of gardening and writing, was a hardy perennial who has died at the age of 92. The tradition started with Gertrude Jekyll (1846-1937) and occupies a minor but honourable place in English literature. Edna Walling, born early in the 1890s, brought her remarkable talents to Australia and Jean Galbraith became her natural successor. Galbraith shared certain characteristics with her cultural antecedents. She was independent, highly professional and utterly devoted to her crafts. Gardening and writing were, to her, indivisible. It was only natural to write of the living things you loved most.

She respected men without entering into intimate relations with them. True, young men were somewhat scarce between the wars when she was of marriageable age, but one suspects that if suitors had knocked on her door she would have rejected them with her sweet courtesy. Most women could marry and have babies, but Galbraith's talents were unique and might have been vitiated by family life.

She was deeply religious and her natural warmth found its focus in loving friendship with those sharing common interests. In her case, this meant with women and men who shared ber passionate involvement with the natural world.

Galbraith was a secondgeneration Australian, her grandparents having emigrated from Scotland to north-eastern Victoria in the middle of the 19th century. Sixty years later, Beechworth was still a prosperous mining town with 50 pubs and Galbraith's grandparents and parents decided this was no place to bring up children.

The extended family moved to Tyers, in central Gippsland, where her

father, too poor to afford anything better, took up land covered with stringy

tussock grass. Their beautiful valley did, however, prove compensation.

Galbraith used the pseudonym "Correa" for her early journalism and for 50 years contributed monthly to two magazines, The Garden Lover and the Victorian Naturalist. She also wrote for The Age newspaper and wrote nine books - or 14 if you count retrospective and expanded editions of her early titles. They ranged from standard texts such as A Field Guide to Wildflowers of South Eastern Australia (1977) and probably her best-known book, Wildflowers of Victoria (1950), to the children's book Grandma Honeypot (1964).

Garden in a Valley (1985) is a charming, discursive account of events in her life, the nearest she came to an autobiography. It is reminiscent of, but less twee than, the tales told by a British writer, the late Marian Cran.

After her parents died, Galbraith continued to develop the garden created

in the year of her birth. She grew plants ancient and modern. She observed

the minutest detail of her plants and knew every centimetre of her garden

and how the times of the day and the days of the year affected her beloved

plants. Sue Forrester of the Melbourne native plant nursery Austraflora

remembers her with affection. Galbraith was a friend of Forrester and her

mother, Gwynnyth Taylor, who was a landscape designer I with Edna Walling.

She lived there until four years ago, and then in a retirement village in Traralgon.

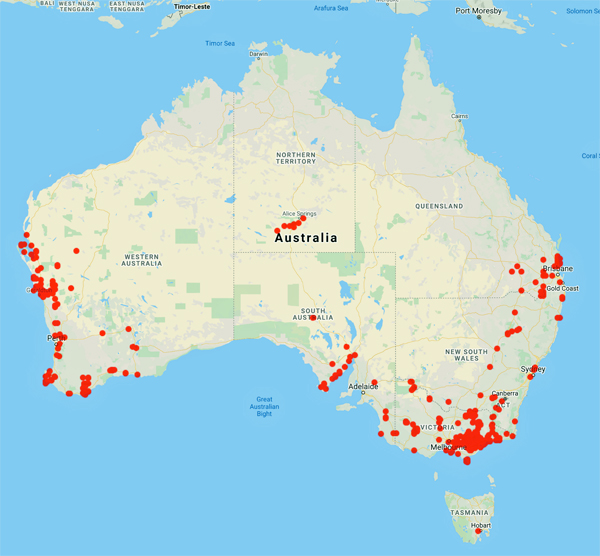

Data from 1,388 specimens