Council of Heads of Australasian Herbaria

Australian National Herbarium

Biographical Notes

|

Council of Heads of Australasian Herbaria |

King, Charles Denison (1909 - 1991)

King, Charles Denison (1909 - 1991) Deny was born in 1909 in the Huon Valley in southern Tasmania, and his early years and upbringing fitted him well for observation and fieldwork. When he had completed only one year of formal schooling, his parents moved to an isolated selection in the Huon hinterland so that their four children would learn to be independent and self-sufficient, living in harmony with nature.

Deny's mother, Ollie, who was in awe of creation in all its diversity, fostered their natural sense of wonder and inspired them with the excitement of discovery. 'We'll find out no end of things for ourselves,' she promised. But she also encouraged them to read, and to write away to the library for books on subjects which fascinated them, such as genetics and bird migration.

Deny's father, Charlie, prospector as well as farmer, imparted his consummate bushcraft, declaring, 'Seeing with your mind what your eyes are looking at is an education on its own'. He frequently admonished his children, 'For goodness' sake, use your eyes!'

Young Deny, with a naturally inquiring mind, was always experimenting. He tried to produce fire by friction, and spent many hours trying to emulate the birds, which were his passion, constructing wings in his attempts to fly. To earn 11-pounds to buy a telescope with which to study the stars, he persisted in the task of snaring, so abhorrent to him but necessary to protect the crops and vegetables from bush predators. He also began his lifelong study of weather conditions, which later led to his becoming one of the Bureau of Meteorology's southernmost observers for 40 years. His ability to predict the incredibly changeable weather which swept in on the south-west from the Roaring Forties became legendary.

Charlie often took Deny on his prospecting expeditions and when the family went exploring, they always took two treasured and much used books, the standard botanical reference, Rodway's 'Flora of Tasmania', and Deny's own precious copy of J.A. Leach's 'An Australian Bird Book'. Charlie, Deny and his older sister Olive were the first Europeans to climb Mount Weld and discover the nearby chain of lakes.

As a young man, Deny ventured further and further into the fastnesses of the south west, and also began to visit the Tasmanian Museum in Hobart in search of information about the plants and creatures he came across. Museum staff, impressed by the quiet bushman with such detailed knowledge of these little-explored areas, enlisted him as a collector. It was the first of many such requests from researchers and scientific institutions throughout the 55 years.

In the 1930s Deny walked twice across the ranges to rarely visited Lake Pedder, and at the end of his life, after travelling to many wild and magnificent places across the world, he still declared it one of the most beautiful scenes he had ever gazed upon. The plant and invertebrate specimens he collected for the Museum became even more important after hydro-electric development flooded Lake Pedder in 1972.

Later in the '30s, Deny spent most of his time at Cox Bight, on Tasmania's rugged south-west coast, where small syndicates had been mining alluvial tin for 40 years. Deny joined his father on their own lease, revelling in new opportunities to explore other wild ranges and the challenging coastline. Then after war service with the AIF as a sapper in the Middle East and New Guinea, where he studied the plants and birds in every spare moment, Deny returned to the south-west for the independent bush life he loved.

He built his home at Melaleuca, named for the vegetation, and over the next 40 years he strode every expanse of button grass plan, climbed virtually every range, descended every gully, crossed every creek and river of the rugged terrain, and sailed into every cove of the great Port Davey waterways and the formidable coast, always aware, alert, and keenly observant. Nothing was too small or insignificant to escape his attention: minute flowers and fungi, tiny moths, little grasshoppers, secretive emu-wrens, or the diminutive galaxiids, so-called native trout, darting through the amber gold water of the creeks which laced the button grass plains.

In the 1950s botanical specimens he sent to the Tasmanian Museum for identification were passed on to the eminent botanist, Dr Winifred Curtis, at the University of Tasmania. She was working on a new book, 'The Student's Flora of Tasmania' and was delighted with the unusual material, which extended distribution patterns for some species.

And so began almost 40 years of significant collaboration.

In 1965, when Deny sent three specimens, Dr Curtis wrote, 'The arrival of your box of treasures caused considerable excitement in the university botany department.' Two proved new to science.

One was a species of Euphrasia, or eyebright, endemic to the peaty heathlands and mountains of the Port Davey area and never before described. With clusters of white, sometimes lilac or deep purplish blue lobelia-like flowers, often striated crimson or purple, set off by small serrated dark green leaves, it is a conspicuous and attractive plant in bloom.

Curtis' description in 'The Endemic Flora of Tasmania' concludes: 'The species is named in honour of Charles Denison King who collected the species designated the type, and who has done much to increase knowledge of the flora of south-west Tasmania.'

Another specimen, Oschatzia saxifraga, was the first fresh material she had ever seen, and extended the known range given in the standard reference, Rodway's 'Flora of Tasmania'.

The third specimen was of even greater interest. It was a plant with grevillea-like, glossy green leaves which Deny had first discovered in 1937 in only one location. Then in 1965 he found another elsewhere. Curtis believed it to be another 'quite new', 'hitherto undescribed' species and requested more material.

Curiosity and enthusiasm well aroused, Deny was delighted to oblige. Early one spring morning he set off on the arduous walk, scrambling and crawling through thick understorey to reach the mystery plant. He dug six suckers and cut a section of the wood, returning home 'a bit tired and very thirsty'. It was a momentous day's collecting. Deny had discovered what is thought to be the oldest plant clone in the world.

In summer he obtained specimens of its crimson flower spikes which Curtis dissected to confirm it belonged to the Gondwana genus Lomatia. It was later named Lomatia tasmanica and given the common names Kings lomatia and Kings holly, in recognition of its discoverer. Being a triploid, having three sets of chromosomes instead of the usual two, it is sterile and reproduces by suckering, which precludes any genetic diversity. Fossil leaves from the area have been dated by radio carbon tests as at least 43,600 years old.

The plant Deny discovered in 1937 seems to have disappeared and the location of the one from which he took specimens has been kept an official secret. The highly endangered plant is now protected by Act of Parliament and efforts are being made to propagate it.

In 1972 Deny was responsible for another amazing find. It was a rare orchid, only once before collected, in 1893 in the Port Davey area by the Reverend John Bufton. It had never been found again anywhere. Bufton had sent specimens to Ferdinand von Mueller at the Melbourne Herbarium, where they remained unidentified for over 50 years before botanist J.H. Willis finally described the plant as a new species.

Then the search was on!

Orchidologist David Jones wrote to Deny describing the challenge, saying 'You are the only person in Australia in a position to refind the species.'

Deny needed no urging. His inveterate curiosity, allied with his keen eye and unique knowledge of the terrain, equipped him well for the search. Within a year, returning from a walk to the Western Arthurs, he found a colony of the tiny orchids in a patch of heathland burnt out several years previously. Curtis wrote, 'You have found Prasophyllum buftonianum, collected in 1893 and not seen since! It is an exciting find.'

The King family made a pilgrimage each year to see the insignificant little green-brown flowers, growing a mere 8-centimetres high. Then one autumn, Deny discovered them growing in a firebreak only a few yards from his house! He had always believed in the age-old practice of fire-farming and this proved to his satisfaction the necessity of burning off to regenerate some species.

In 1974 Deny's help was again sought, this time collecting a species of banksia, described by Robert Brown, Matthew Flinders' botanist in 1802. Deny sent specimens of ancient banksia fragments he had unearthed at the mine. He believed them to be undescribed, but scientists thought they were probably the common species Banksia marginata, so they joined the uncatalogued backlog.

Finally analysed shortly before Deny's death in 1991, they were recognised as a hitherto unknown species, now extinct. They had been preserved in a sedimentary bed at least 38,000 years earlier. The species was named Banksia kingii in recognition of Deny, and the description reads, 'He discovered the deposit, encouraged its study and gave freely of his local knowledge and hospitality.'

Source: Christobel

Mattingley, on Robyn Williams' ABC Radio program Ockhams Razor broadcast

Sunday 16 February 2003

Portrait Photo:Extracted from: Tasmanian Archives : Jack Thwaites Collection (NS3195/1/1885)

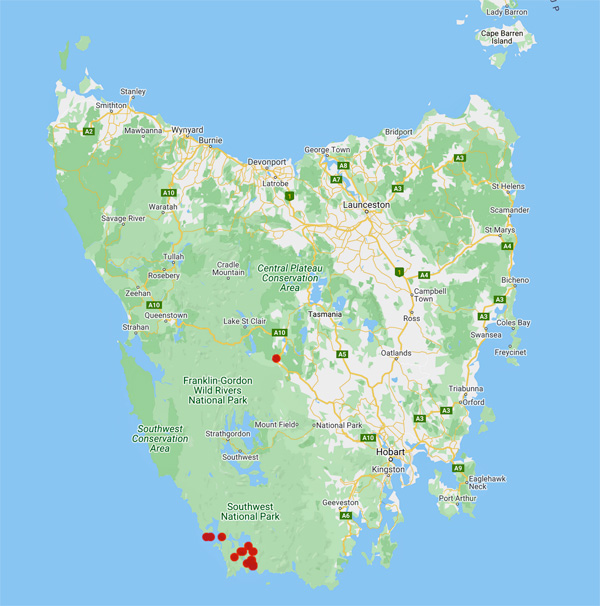

Data from 97 specimens