Council of Heads of Australasian Herbaria

Australian National Herbarium

Biographical Notes

|

Council of Heads of Australasian Herbaria |

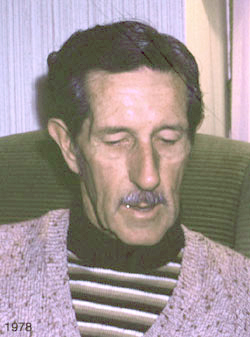

Mair,

Herbert Knowles Charles (1909 - 1999)

Mair,

Herbert Knowles Charles (1909 - 1999)Herbert Knowles Charles Mair was born in Toongabbie, NSW on 8 April 1909. He died in Sydney on September 1999.

He was educated at Narrabeen Public School and Sydney Grammar School, he graduated from the University of Sydney with first class honours in botany. For the rest of his life, Mair was a botanist who loved the knowledge of plants.

His first appointment was to the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) as assistant agronomist in pasture research in 1931. In 1936, at a time when the Northern Territory was only vaguely known to most people, Mair became the first resident botanist in Darwin. He established a herbarium there, and acted in many positions, his formal title being Superintendent of Agriculture and Curator of Botanic Gardens. This position gave Mair a general knowledge of plants including tropical planting, and developed his independence. On a recent return visit to Darwin, he made contact with the current director, who was appreciative of his keen memory for detail. Much of the history of the Darwin Gardens had been lost with World War II and in Cyclone Tracy. Mair was able to identify photographs, sketch the layout of the Gardens, and contribute information for a display of typical Darwin suburban plantings of the 1930s.

World War II changed Mair's priorities and he enlisted in the AMF in 1941, transferring to the AIF in 1942, where he had the rank of captain. He served in farm units in the Northern Territory and New Guinea as forest botanist in New Guinea, Labuan and Sabah.

On his discharge in early 1946, Mair started his 24 years with Sydney's Botanic Gardens as a botanist; he became senior botanist in 1948, and director and chief botanist in 1964 (reorganised as divisional chief, Royal Rotanic Gardens and National Herbarium, in 1968). He retired in 1970.

While in the chair, Mair always insisted he was first a botanist; he was proud of that. He administered with precision and professionalism, but was plagued by a shortage of resources and disappointed at not getting funds for a much-needed new herbarium building.

His efforts were maintained by his successors and were eventually successful. Mair was delighted at the acquisition of land for the Mt Tomah Botanic Garden, and his continuing interest even after retirement caused a later director, Carrick Chambers, to dub him the Godfather of Mt Tomah. The garden opened in 1987, proof that there can be results even after retirement.

He was highly delighted to have been invited to the opening of the garden, and little wonder: he had had the foresight to establish ecological work from the Sydney gardens.

Additionally, he had overseen the revitalisation of Centennial Park and had initiated new, major tree plantings, the first since the 1930s. Mair was greatly concerned about the condition of some of the glasshouses, and had planned and built the first big new pyramidal environment controlled glasshouse in the Gardens in 1970-71.

Not everybody knew of his love of native orchids. A colleague once told him that a horse named Cymbidium (an orchid found widely in Asia, Africa and Australia) was racing; he wagered on it and won at 8/1. Mair also wrote a foreword to Lionel Gilbert's biography of the Rev H. M. R. Rupp (The Orchid Man, 1992).

Not surprisingly, most people who work at the Sydney gardens grow to love them. Mair once wrote a bulletin - The Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney (1970) - stressing particularly that "In these gardens began the agriculture and horticulture of a continent. The first farm in Australia was established on this site with seeds and plants brought from the First Fleet in 1788."

While his precision and punctuality may have been unwelcome at times within his family, his staff appreciated it. He was reliable in all that he did; he was a scientist, a thinker, perhaps a rather private man, but withal, a botanist.

He imbued his family and friends with a knowledge of plants and their botanical names and a great love of the Australian bush. Bushwalking with Mair led to the discovery of delicate flowers and plants and he would demonstrate their beauty in detail through his lens, which was his constant companion.

His own gardens reflected some of his thoughts. They were never neat, landscaped affairs; rather, they were crammed with a wide variety of plants, exotic and native, and incorporated individual pools carved in sandstone especially for his granddaughters. When he was living at South Coogee, he referred to his seaside garden as the South Coogee Research Station, where he had great interest in seeing which species could withstand the sea spray.

I will always remember sharing a room with him before he became director; we talked of many things, and yet at that time he was Mr Mair to me, as was the custom in those days for a younger and junior person. But he confirmed our friendship by giving me the right to call him Knowles. He was like that; I knew this was not just an idle thought. I have valued his friendship of some 53 years.

A man of great complexity, yet simple needs, he was a romantic who loved and shared his enthusiasm for poetry, play-reading, theatre, music and the moderate imbibing of Guinness, to which he attributed his longevity.

He is survived by his wife, Joan, her two boys, David and Ian MacDonald, to whom he was father, six granddaughters and four great-grandchildren.

George Chippendale (1999)

From The Sydney Morning Herald OBITUARIES

Data from 518 specimens