Council of Heads of Australasian Herbaria

Australian National Herbarium

Biographical Notes

|

Council of Heads of Australasian Herbaria |

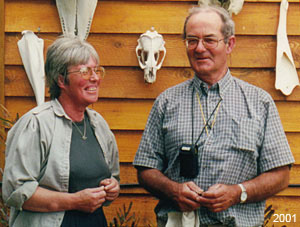

Wapstra, Hans & Annie (1943 - ) (1942 - )

Wapstra, Hans & Annie (1943 - ) (1942 - ) We were born (May 1943 and April 1942) and educated in Holland.

We arrived in Australia in 1970 as migrants on an assisted passage. We were among the lucky ones who came on a P&O cruise ship that took us through the Panama Canal, via Fiji and some other wonderful places, and landed us in Sydney. Hans had just finished a major degree in forestry at the University of Wageningen where Annie had been a secretary at one of the forestry departments.

Forestry in Holland had by then become multiple use, and forest management focussed increasingly on conservation and recreation values, rather than wood production. Hence the forestry degree had a major component of wildlife population dynamics, plant ecology and nature conservation. The latter included management of deer populations through hunting.

It gave Hans a job with the Tasmanian Animals and Birds Protection Board. which in 1971 was amalgamated with the Scenery Preservation Board to become the Tasmanian National Parks and Wildlife Service. How old-fashioned this all sounds now. Over the years deer management became game management (deer, duck, wallaby, possum and so on). In the 1980s the job grew to include wildlife parks, and then whales.

Both of us could be best described as naturalists with a broad interest in all sorts of things, but with a strong focus on flora. When we arrived in Tasmania we found we could recognise very little of the flora, except of course, introduced weeds native to Europe. Orchids seemed an ideal family to come to grips with, as there were only 145 species, and orchids were very rare in Holland and had a special fascination for us.

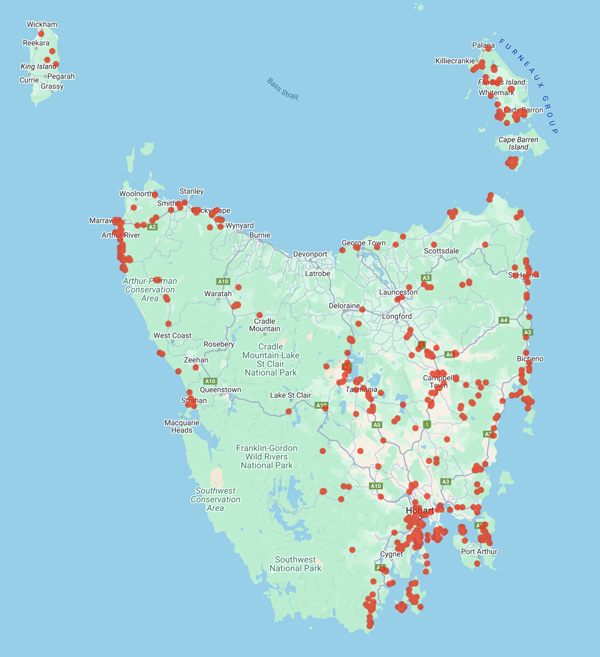

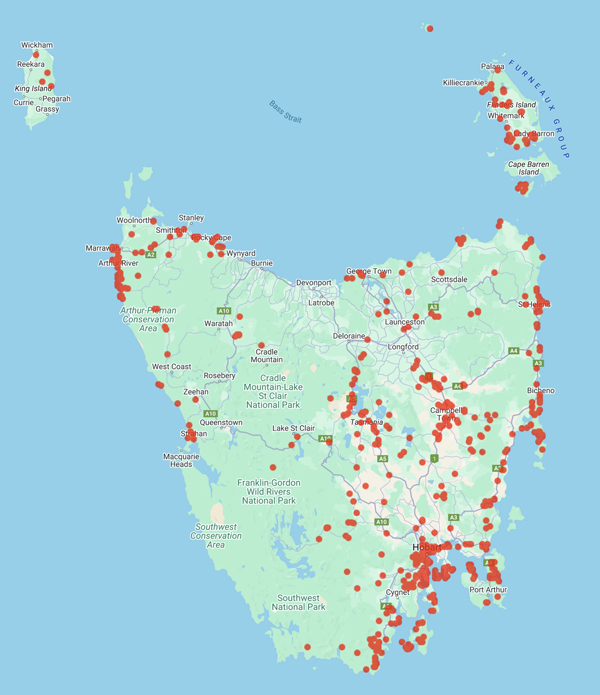

After the first few years when we got to know the more common orchids, we became discouraged as the available literature on orchids was less than helpful. We kept finding plants that did not want to be keyed out, and in the end we often gave up trying. It was not until the early 1990s that the orchids took a firm grip on us again. The Parks and Wildlife (under a new name with every political change) had by then developed a strong Flora Section, which had secured funding for a project to map Tasmanian orchids.

This got us involved again, and brought us into contact with David Jones and the Orchid Research Group. On revisiting orchid colonies that refused to be slotted into known Tasmanian species, more often than not they belonged to a group with a confused taxonomy or they were a new species altogether. In short, we were no longer working in isolation, we were not that dumb after all, and we were in for a very stimulating time that kept us busy most weekends.

A few years later, departmental duties had changed from fauna to 50/50 whales/orchids and then full time orchids and threatened flora. Orchids had come of age in Tasmania. During this time we were able to travel more widely, with Annie always able to come along as an unpaid volunteer on surveys, and on collecting trips to try and find plants requested by David Jones for his revision of the Tasmanian Orchidaceae. A hobby had become a rewarding job, and we feel quite privileged as working in the public service is not meant to be that much fun.

We both got deeply involved in the production of The Orchids of Tasmania, some in departmental time but much of it at night and in weekends, got involved with native grasslands and its many threatened species, including orchids. Over time we developed some plant photography skills and when early retirement came in August 2001, we found we were flat-out doing all the things we had been doing be it now as a hobby again.

That is what orchids did to us. It could be genetic as one of our kids has the bug as well.

Source: Hans & Annie Wapstra, pers com (2002), photo supplied.

Data from 1,460 specimens

Data from 1,109 specimens