|

Episodes in Australian Bryology

The 1890s and later

By the turn of the 20th century a number of resident Australians were studying bryophytes seriously. Certainly specimens were still being sent to European bryologists, still home to the majority of the world's bryological experts, but often this was done after an initial examination in Australia. By now accounts of Australian bryophytes were appearing in Australian journals, so making the information more easily available to those in Australia who wished to study the bryophytes.

The period into the 1920s saw much investigation of the Australian bryophytes by both Australian and overseas people but then there was little work until the 1950s. Even when Australia's bryophytes were being studied during the first half of the 20th century the work was not consistent across the country. For example the Tasmanian bryophytes received much attention. On the other hand the Victorian botanist James ("Jim") Hamlyn Willis (1910-1995), writing in 1955 about the Victorian state of affairs, noted that between 1905 and 1947

...no additional records were made to the State's moss flora...and the situation with the State's hepatic flora is as bad, or worse...

Certainly the disruption caused by Depression years, the Second World War and the recovery period in the first few post-war years would have hindered work on bryophytes. However, during those decades botanical work in general did not come to a stop. Botanists were still employed and field work was still being undertaken, even if not on a grand scale but bryophytes were generally ignored. Jim Willis observed that

...organized natural history expeditions to unfamiliar parts of Victoria (e.g. to the Mallee and Lady Julia Percy Island) within the past quarter of a century have, almost without exception, failed to take stock of the Bryophyta – surely the easiest and least bulky of all plants to collect.

Willis noted that in 1944 the New Zealand bryologist GOK Sainsbury had written:

Bryological research on the Australian continent has been so desultory that it is impossible to estimate the probability of any future discovery

.

Yet, within a decade of Sainsbury's pessimistic observation work on Australian bryophytes was picking up. The second half of the 20th century has seen a great increase in what's known about the Australian species, though there are still many gaps in that knowledge. If there is to be a good understanding of the world's bryophytes, those found in Australia cannot be ignored. To do so is to bias conclusions about such topics as the evolution and dispersal of the world's species. The past few decades have seen both Australian and overseas bryologists studying Australian bryophytes and that will undoubtedly continue to be the case for many years.

The early decades

Thomas Whitelegge (1850-1927) was born in England and migrated to Sydney in 1882. He had varied biological interests and published many studies on various groups of invertebrates. He became an authority on the mosses of New South Wales and compiled a list of about 300 moss species for the state but the list remained unpublished. Whitelegge collected numerous specimens at the behest of the Finnish bryologist Viktor Brotherus who was engaged in a study of the world's mosses and Whitelegge's collections were the basis for many new species.

Whitelegge's contemporary, the Reverend William W. Watts (1856-1920) was born in England and arrived in Australia in 1887. Watts collected in New South Wales (including Lord Howe Island), Queensland and Victoria. His collection of 12,000 moss specimens and several thousand liverworts is now housed in the New South Wales herbarium in Sydney. Watts corresponded and exchanged specimens with several European bryologists and, alone or in collaboration, published a number of important papers about Australian bryophytes – especially the mosses. Watts met Whitelegge in 1898 and together they published the two parts of the Census Muscorum Australiensium. A classified Catalogue of the Frondose Mosses of Australia and Tasmania, collated from available Publications and Herbaria Records. The first part appeared in 1902 and the second in 1906.

The authors realized that the catalogue was likely to contain errors and, in the introduction to Part I, wrote:

The inaccessibility of specimens, and even, in some cases, of descriptions, the differing principles of determination adopted by specialists, and the large number of new species of which we know nothing except the names, makes an unchallengeable list of Australian Mosses impracticable at the present stage.

With regard to the "differing principles of determination" adopted by different bryologists, Watts and Whitelegge made the following comment:

To illustrate one of our many perplexities, Mitten and Wilson introduced an excessive number of European and Antarctic names into our Moss Flora. Dr. Carl Mueller, on the other hand, regarded all our species as endemic

.

William Anderson Weymouth (1841-1928) and Richard Austin Bastow (1840-1920) were accomplished amateur bryologists who contributed significantly to the knowledge of Tasmanian bryophytes. Weymouth was born in Tasmania and worked as an insurance assessor with the National Mutual Insurance Company. He built up an extensive bryophyte collection, corresponded with several European bryologists and published several papers about Tasmanian bryophytes. One of his correspondents, the Finnish bryologist Viktor Brotherus, named the moss genus Weymouthia in honour of Weymouth![]() .

.

Bastow was born in Scotland to English parents and trained as an architect. He arrived in Tasmania in 1884 (with an intervening elopement to the United States behind him) and was appointed City Surveyor of Hobart. He spent much time collecting and studying bryophytes and published a number of papers about Tasmanian bryophytes in the Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania, his first in 1886. There had been no detailed account of the Tasmanian bryophytes since those presented by Mitten and Wilson in the younger Hooker's Flora Tasmaniae of 1860. There had been many additions to the bryophyte flora of Tasmania since then and Bastow wrote two long papers to present an up-to-date account of the state's bryophytes. The first, "Tasmanian Mosses", was presented at a meeting of the Royal Society of Tasmania in 1886, contained species' descriptions and was accompanied by an illustrated identification key to the genera. That key was presented on a large fold-out sheet, about 110 centimetres long and 60 wide. You can find some more details in BASTOW'S MOSS CHART CASE STUDY.The paper was also published as a separate booklet in 1886, with a blank, lined sheet between each pair of printed pages, which allowed users to make additional notes of their own. The second paper, "Tasmanian Hepaticae" was presented a year later, contained a written identification key to the liverworts and hornworts and was complemented by 43 pages of drawings that illustrated many of the species.

Here are two of illustrations from Bastow's "Tasmanian Hepaticae" paper:

|

|

Bastow wrote the two papers with a view to making basic identification information readily available to a wide audience. In the introduction to the moss paper he wrote that the illustrated key was prepared "... chiefly for the use of students, residing in our country districts, who have not at all times access to the many valuable Botanical works in the Royal Society's Library". He expressed a similar sentiment in the introduction to the second paper: "... those who reside far away from the city and are desirous to know something about the Hepaticae ... but have no hand-book on the subject that they can consult, I may venture to hope that the following compilation may to some extent be useful, its many shortcomings notwithstanding". At the beginning of the second paper, Bastow made some comments that often still hold today:

In popularly written botanical handbooks the Hepaticae are usually not described, the authors chiefly confining their attention to plants of larger growth. The phanerogamous plants receive full notice; the Ferns and Lycopods may also be described; but here the line is usually drawn. The Mosses, Hepaticae, Lichens, and Fungi are dismissed with some such remark as that they are distributed throughout the world, and are of no economical importance; or that they form beautiful transition from low to high organisation, and that they are evascular.

It is still the case that many books titled or promoted as "Flora of..." or "The plants of..." some state or region don't include the bryophytes – even though bryophytes are plants and therefore part of the flora.

The Bastow family moved to Melbourne in 1888 and in a letter to a friend Bastow wrote that "... I had to part with my beautiful microscope in order to pay every account that I owed in Tasmania before I left ...". That would have been a significant loss, a microscope being an essential tool for a bryologist. In addition, his work at first left little time for botanising but over his remaining years he did amass a large collection of bryophyte specimens, mostly from areas now contained with the greatly enlarged city of Melbourne and published a brief account of the Victorian liverworts. His specimens and papers are held at the herbarium and library at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Melbourne![]() .

.

Leonard Rodway (1853-1936) was born in England and arrived in Tasmania in 1880, where he practised as a dentist. He had a great interest in botany, published many papers about the Tasmanian flora and was appointed Tasmania's Honorary Government Botanist in 1896. Rodway was a very accomplished bryologist and published a number of papers about Tasmanian bryophytes. These were later gathered into two short monographs: Tasmanian Bryophyta, Volume 1, Mosses (which appeared in 1914) and Tasmanian Bryophyta, Volume II, Hepatics (the corresponding liverwort and hornwort monograph which appeared in 1916). Rodway intended the volumes to be a critical account of the Tasmanian species, with careful assessment of the right of inclusion of each species. It is worth quoting a large part of the introduction to his moss volume:

The Tasmanian Bryophyta have received a considerable amount of attention by both collectors and specialists, and the results of their labours are recorded in many different publications. Only two efforts have been made to compile the descriptions, first, in Hooker's noble "Flora Tasmaniae," published very many years ago, and, second, in Bastow's excellent little Handbooks of the Mosses and Hepatics. Unfortunately, many errors have crept in, and plants have been recorded as Tasmanian that probably do not live here.... But the principle reason why a revision of the group is at present justified is because the persistent labour of W.A. Weymouth has added about a hundred and fifty new species to our list; besides which he has submitted his large collection to European experts...

The work will not be a mere compilation, but the descriptions will all be original from the specimens in Archer's, Weymouth's, and my collections, and, with few exceptions, these have been identified by the above-mentioned experts. Very few others will be included, and where this is so, full mention will be made. Otherwise all plants that cannot be verified will be excluded. This will, perhaps, mean rejecting some that should be included, but as this is intended somewhat as a new departure, it is best to go as far as possible in eliminating erroneous identifications.

Hiatus and resurgence

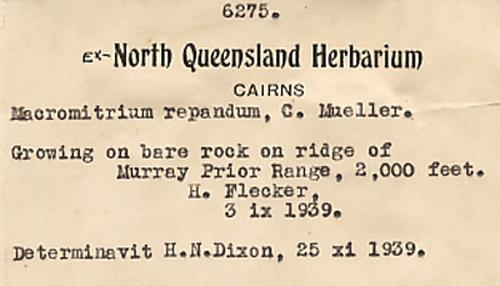

Rodway published two more papers, in 1918 and 1926, in which he noted some Tasmanian liverworts. Alan Burges, of the University of Sydney, published two updates to the Watts & Whitelegge moss catalogue in 1932 and 1935. In 1932 the New Zealand bryologist GOK Sainsbury published four papers about Australian mosses in the Victorian Naturalist, the journal of the Field Naturalists Club of Victoria and in 1935 his compatriot KW Allison published a paper about Australian liverworts in the same journal. These were aimed at helping amateur naturalists who were interested in studying bryophytes and provided some advice on how to study bryophytes as well as descriptions of a small number of species. However, in general the 1930s and 1940s saw virtually no bryological activity in Australia and also fairly few publications about Australian bryophytes by northern hemisphere bryologists. The latter certainly made use of the older Australian material already held by northern hemisphere herbaria but there was still some overseas despatch of Australian specimens occurring. For example, in 1942 the Proceedings of the Royal Society of Queensland contained an 18-page paper titled "Additions to the Moss Flora of North Queensland", by the English bryologist HN Dixon and he began by writing:

For some time past I have been receiving specimens of mosses for determination from the North Queensland Naturalists' Club, sent by various collectors and mostly from the neighbourhood of Cairns. They continue to show an interesting bryological flora, some localities, for example the rain forest area and Mt. Bartle Frere, suggesting promising new fields of study.

Dixon 's paper mentioned many collections made in the latter half of the 1930s and at least one from 1940.

After war service with the RAF Alan Burges became professor of botany at the University of Sydney in 1947, published a taxonomic paper about the moss genus Dawsonia in 1949 and moved to England in 1952. In the 1950s Jim Willis became a significant contributor to knowledge of Australian bryophytes and during that decade published a series of papers, mostly about mosses, in the Victorian Naturalist. In those papers he recorded many mosses not previously found in Australia, amongst which were several new species. Those records were based on his own field work in various parts of Australia as well as specimens sent by correspondents from many parts of Australia. Willis corresponded with and received much advice from Sainsbury, whose Handbook of the New Zealand Mosses was published in 1955. This monograph, with its written descriptions and illustrations, was much used in Australia since many mosses are common to the two countries. The decade saw bryological work by several other Australians, including the publication of the first paper to record an Australian bryophyte fossil - a fossilized moss capsule from the brown coal deposits at Yallourn in Victoria![]() .

.

|

The late 1940s and, more so, the 1950s also saw some work on Australian bryophytes by overseas bryologists. For the most part this consisted of the citation of some Australian specimens in the course of general studies, rather than work specifically on Australian bryophytes. There were some exceptions. For example, the American Edwin Bunting Bartram (1878-1964) published papers specifically about the mosses of Western Australia and Queensland in 1951 and 1952. Between 1953 and 1956 Sainsbury published ten papers about Tasmanian mosses, mostly studies of the specimens that had been in Rodway's herbarium.

The later 20th century and beyond

These pages on the subject of Australian bryology are deliberately called Episodes since they give highlights rather than an account of all the work that has been done on Australian bryophytes. Such an account would demand considerable space, especially so when it comes to the later 20th century which has seen a resurgence in studies of Australian bryophytes, by both Australian and overseas bryologists. The paper given in the following reference button gives numerous names and very short summaries, often just a few words, of how those people have contributed to the study of Australian mosses![]() .

.

There would be little point in trying to include all that on this website, nor in attempting to produce an equivalent, telegraphic summary of work on the liverworts and hornworts. However, to give you some idea of the range of research that has been going on recently, one of the case studies looks a little at WHAT'S BEEN HAPPENING SINCE 2000.

The later 20th century saw the appearance of three major monographs that provided illustrations and detailed descriptions of the bryophytes of southern Australia. These books brought together information that, previously, had either not been available or which could be found only in scientific journals. By making much information easily available these HANDBOOKS OF THE LATER 20TH CENTURY gave further impetus to the study of bryophytes in Australia.

Bryophytes in Australian herbaria

If Australian bryophytes are to be studied they need to be collected. If bryophytes are to be studied in Australia then bryophyte specimens need to be held by Australian herbaria. By the mid-1800s specimens of Australian bryophytes were already being collected, mostly to be sent overseas. In the later 1800s it became more common to collect enough material to keep some of each sample in Australia and send some to a European expert. Through the first half of the 1900s the numbers of bryophyte collections held in Australian herbaria increased, albeit not uniformly in each state. With the resurgence of post-1950 bryological activity in Australia there was an increase in field work and the accumulation of specimens from a greater variety of locations.

Amateurs as well as professionals have added to the bryophyte collections in Australian herbaria during the 20th century. Two examples of amateurs, from quite different parts of the country, are Hugo Flecker (1884-1957) and Alexander Clifford Beauglehole (1920-2002). Flecker, a radiologist, moved to Cairns from Melbourne in 1922. He had wide interests in natural history and became foundation president of the North Queensland Naturalists Club. Flecker, and other members of the Club, sent north Queensland specimens to the English bryologist HN Dixon, but also kept material in the Club herbarium. Many of the bryophyte specimens from the Club herbarium are now held at the Australian National Herbarium in Canberra. By profession Beauglehole of Portland in Victoria was an orchardist and was another example of a person with wide interests in natural history. As well as collecting in western Victoria he travelled widely through central, northern and western Australia and has added numerous bryophyte specimens from many isolated locations to the herbarium at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Melbourne.

|

Jim Willis was a professional botanist at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Melbourne with a strong interest in the bryophytes and he has already been mentioned above, in connection with the beginning of the resurgence in Australian bryology in the 1950s. He was also an energetic worker in the field and collected numerous specimens from many parts of Australia from the 1950s onward. He had a high standing with the international botanical community and was also generous with his bryological knowledge to interested amateurs, for example to fellow members of the Field Naturalists Club of Victoria which he had joined in 1932. The other late 20th century Australian bryologists mentioned above or in the WHAT'S BEEN HAPPENING SINCE 2000 CASE STUDY have also added considerably to the bryophyte collections in Australian herbaria. Another significant professional collector was Heinar Streimann (1938-2001) who spent much of his working life employed by the Australian National Botanic Gardens in Canberra. By his own admission he preferred field work to bench work and his contribution to Australian bryology was largely through his field work in many parts of non-inland Australia, beginning in the 1970s. He collected most often in the tropical forests or the well-watered parts of the south-east and did much to build up the bryophyte collections at the Australian National Herbarium in Canberra. He generally left it to others to work on his collections, often despatching loans or duplicates of his material to other bryologists, in Australia or overseas. His collections were therefore used by many bryologists. Given the extent of his field work it is not surprising that, amongst the Streimann collections, other bryologists often found interesting specimens. Some were of species that, though known from elsewhere, had not yet been recorded from Australia or which greatly extended the known locations for species already known from Australia. From time to time Streimann collated and published the results of such identification work by other experts, so making the results of the work available to a wider audience and increasing knowledge of Australian bryogeography. A number of bryologists also described new species based on material collected by Streimann. Though his major contribution was through his collecting he did publish taxonomic studies on several moss genera and, at his death, left behind a largely completed manuscript and illustrations of the mosses of Norfolk Island. The work was published posthumously as a book.

More field work is still needed, for there are areas of Australia that are still poorly known from a bryological perspective. However, the collecting activities of amateur and professional bryologists in the later 20th century has greatly increased the herbarium holdings that are essential for research.

Many bryophyte species are widespread in the world so Australian bryologists benefit from having access to accurately identified specimens from overseas. If a bryologist suspects that he or she has found an Australian specimen of a species that has thus far been known only from overseas, it can be useful to have an overseas specimen of that species, for comparison with the Australian specimen. One relatively inexpensive way of acquiring overseas material is by exchange and a number of Australian herbaria exchange excess Australian material with overseas herbaria which have excess material from non-Australian locations. There is also an active loans program between Australian and overseas herbaria. Australian bryologists often borrow material from overseas herbaria and material in Australian herbaria is loaned to overseas researchers.

Australasian Bryological Newsletter

Australasian Bryological Newsletter

There is no formal Australasian bryological society but there is an active informal network supported by the Australasian Bryological Newsletter. The Newsletter began in 1979 to serve the interests of amateur and professional bryologists in Australia and New Zealand. It appears twice a year and provides news and information on research, workshops and other bryological activities in the Australasian region. Bryophyte workshops are held every two to three years, in different parts of Australia, giving bryologists a chance to meet and work together. The idea of a Newsletter arose during the first of George Scott's bryophyte workshops in 1979. For a few years the Newsletter was produced by Helen Ramsay, of the University of NSW, and Patricia Selkirk, of Macquarie University with additional help from Alison Downing, also of Macquarie University. Helen Ramsay has contributed much the knowledge of the cytology of Australian mosses and has also published on the taxonomy of various families of mosses. Patricia Selkirk has made significant contributions to the study of Antarctic and sub-Antarctic mosses. Alison Downing is well-known for her studies of Australian bryophytes growing on calcareous substrates.

The Newsletter issues from number 42 onward are available online at:

Helen Ramsay features in the Newsletter's 49th issue, published in 2004, the year of her 75th birthday:

![An Australian Government Initiative [logo]](/images/austgovt_brown_90px.gif)