Aboriginal use of fungi

An

excellent source of information about this topic is the chapter by Arpad Kalotas

in Fungi of Australia, Volume 1B and virtually all the material in this

section is taken from there.

An

excellent source of information about this topic is the chapter by Arpad Kalotas

in Fungi of Australia, Volume 1B and virtually all the material in this

section is taken from there.

For thousands of years Aboriginal fungal lore and knowledge has been passed orally from generation to generation. The written record began in the 19th century, when various European settlers and explorers recorded Aboriginal uses of and beliefs about fungi. Unfortunately, in most cases there is not enough detail to allow identification of the species involved. It also pays to use early European accounts carefully, for in any cross-cultural contact there is potential for misunderstanding and therefore mis-reporting. It should be no surprise to learn that the early Europeans recorded varied attitudes to fungi amongst the different Aboriginal people of Australia. After all, if you look at the different cultures across the same size area in Europe you'd find the same varied attitudes to fungi.

In 1841 the explorer George Grey published an account of his travels in Western Australia and reported that he'd seen seven species of fungi eaten by the Aborigines. He commented that "The different kinds of fungus are very good. In certain seasons of the year they are abundant, and the natives eat them greedily". The Tasmanian George Robinson wrote: "Various are the fungus which the natives eat, and all are known to them by different qualities which they possess, and all are known by different names".

Kalotas notes a Central Australian belief, as recorded by the anthropologists B Spencer and FJ Gillen at the beginning of the 20th century: "Falling stars appear to be associated with the idea of evil magic in many tribes. The Arunta believe that mushrooms and toadstools are fallen stars, and look upon them as being endowed with arungquiltha (evil magic) and therefore will not eat them." However, Kalotas comments that this cannot apply to all fungi, for a number are eaten by the central Australian people.

|

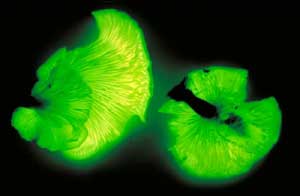

Omphalotus nidiformis, left, and luminescent in the dark, above. |

James Drummond, an early settler and plant collector in Western Australia talked of a large luminous mushroom (most likely Omphalotus nidiformis) and reported that several Aboriginal people, when they saw it "...cried out 'Chinga!' their name for a spirit, and seemed much afraid of it".

Interestingly, several of the early European accounts report that Aborigines did not eat species of Agaricus - the genus which includes the Common Field Mushroom.

While a number of people in the 20th century have documented Aboriginal fungal use, it is worth making special mention of John Cleland . He had broad scientific interests, including anthropology, was a very knowledgeable mycologist and so contributed significantly to knowledge of fungal use.

There is still much scope for ethnomycological fieldwork in Australia. Very few useful fungi have been recorded and it is possible that there is more knowledge still in peoples' heads. Geographically, there are large blank areas with no recorded uses, but away from the desert areas much native knowledge has probably been lost due to more concentrated European settlement and agriculture. But, who knows what can be found from papers and diaries still sitting in libraries or archives. It would also pay to check the published statements in some of the early European writings and to confirm species identifications. For the moment, here are the uses of the fungi reported in the chapter by Kalotas.

Choiromyces aboriginum

This truffle-like fungus is found in the dry areas of South Australia, Western Australia and the Northern Territory. It is roughly spherical in shape and grows to about 7 centimetres in diameter. The fruiting bodies will slightly push up the overlying soil, cracking it and such cracks are used to help find the fungus. It is a traditional native food and has also been used as a source of water. The fruiting bodies were eaten raw or cooked and Kalotas reported one experience, as follows:

"They were cooked in hot sand and ashes for over an hour, and then eaten. They had a rather soft consistency (a texture akin to that of soft, camembert-like cheese) and a bland taste. Cooked specimens left for 24 hours and then reheated developed a flavour like that of baked cheese."

Cyttaria gunnii

Cytaria gunnii |

In Australia this fungus grows only on Nothofagus trees in Tasmania and southern Victoria. The fruiting bodies are yellow to orange and golfball-like in appearance. The fruiting bodies were eaten and also contained a fluid that was of "pleasant taste" to George Robinson, in the first European account of the use of this fungus, in 1833.

Laccocephalum mylittae (formerly called Polyporus mylittae)

This fungus is commonly called Native Bread and produces a sizeable and valued, underground sclerotium, that was eaten raw or roasted and has been described as having the flavour of boiled rice. Personal experience of a specimen collected near Braidwood, showed it to have a nondescript taste. The consistency is firm and occasionally sclerotia could grow to the size of a football. This Fungimap link [http://fungimap.rbg.vic.gov.au/fsp/sp090.html] shows the distribution of the fungus. Aborigines often found the sclerotium by smell, sometimes by pushing a stick into the ground as they walked along and smelling the stick after pulling it out.

Laetiporus portentosus (formerly called Piptoporus portentosus)

What is probably this species of polypore, was eaten by Aborigines in Tasmania, possibly as an emergency food. In Tasmania, South Australia and Western Australia a fungus, sounding like this one, was used as tinder and to carry fire as it would smoulder all day. In the northern hemisphere also, several polypores have been used as tinder or for carrying fire. Fomes fomentarius [web link] and Piptoporus betulinus [web link] are two examples. Notice the resemblance in outward appearance between Piptoporus betulinus and Laetiporus portentosus. This will help you understand why the latter was once thought to belong in the genus Piptoporus.

Mycoclelandia bulundari

This is another desert truffle-like fungus, known from the Northern Territory and Western Australia, and grows to about 10 centimetres in diameter. It is eaten after being cooked in hot sand and ashes, and Kalotas reports it as having a strong mushroom flavour. He also cites other reports of its being used as a medicine (fluid from the fungus being used on sores and in sore eyes), rubbed into armpits and "when rubbed into the hair it prevents growth". While on the subject of desert truffles, it is interesting to note that desert truffles (in the genera Terfezia and Tirmania) are sold in Arab markets.

Phellinus sp.

Phellinus sp. |

Many species of polypore genus Phellinus are hard, woody bracket fungi,

mostly coloured dark bronze to black and often with the upper surface heavily

cracked. Aborigines have used Phellinus fruiting bodies medicinally.

The smoke from burning fruit bodies was inhaled by those with sore throats.

Scrapings from slightly charred fruiting bodies were drunk with water to treat

coughing, sore throats, "bad chests", fevers and diarrhoea. Unfortunately

there is some uncertainty about which species of Phellinus were used.

Phellorinia herculeana

This powdery-spored species of desert areas was used, liked Podaxis pistillaris, for body decoration.

Pisolithus sp.

When fully mature, the fruiting bodies of Pisolithus species produce copious amounts of powdery spores. Before that, much of the fruiting body will have a tarry consistency and at that stage it was used on wounds. It was also eaten when still very young, but most likely as an emergency food. In various published accounts you will see the name Pisolthus tinctorius used. This overseas name has been used almost automatically (and probably incorrectly) for Australian Pisolithus specimens.

Podaxis pistillaris

While commonly thought of as a "Stalked Puffball", this powdery-spored desert fungus is not closely related to puffballs. It was used by many desert tribes to darken the white hair in old men's whiskers and for body painting. As you'd expect from this map [http://fungimap.rbg.vic.gov.au/fsp/sp042.html] of its distribution, the fungus was used by many desert Aborigines. There are reports of its also being used as a fly repellent. Apart from the more common, ground-inhabiting Podaxis pistillaris, there is one other Podaxis species in Australia - Podaxis beringamensis, found on termite mounds and presumably both species were used.

|

Purple spores used as a 'powder puff' by an Aboriginal elder from Mount Liebig, 1930s (right) |

|

Pycnoporus sp.

The fruiting bodies of this polypore genus look like bright reddish-orange

brackets and are widespread on dead wood. In Australia there are two species

- Pycnoporus coccineus and Pycnoporus sanguineus, with overlapping

distributions. Moreover, the two species are similar in appearance, so without

specimens there will be doubt as to which Pycnoporus species is meant

in any particular account. One or other Pycnoporus is used medicinally

in a variety of ways by desert Aborigines - "sucked to cure sore mouths",

rubbed inside the mouths of babies with oral thrush, rubbed on sore lips. It

has also been used as a teething ring. Out of curiosity, and after hearing of

the Aboriginal use of this fungus, one person in Canberra chewed on a Pycnoporus

specimen to see if it would have any effect on a small mouth ulcer. The ulcer

soon disappeared, so at least the fungus had no detrimental effect. Of course,

in this case, there is still the question of whether chewing the fungus cured

the ulcer or whether its disappearance was coincidental. Two antibiotic compounds

have been found in Pycnoporus coccineus.

"Mulga Bolete"

An unidentified bolete species, found growing in the Mulga woodlands of Central Australia, is eaten after being cooked in hot sand and ashes.

![An Australian Government Initiative [logo]](/images/austgovt_brown_90px.gif)