![Director of National Parks [logo]](/images/dnp_90px.gif)

![Director of National Parks [logo]](/images/dnp_90px.gif) |

|

|

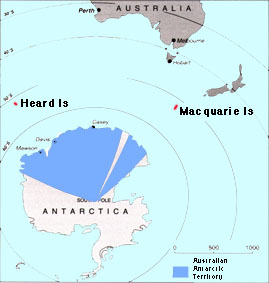

Look for Macquarie Island on a globe and you will find real meaning in the term 'down under'.

The fact that this subantarctic island is almost out of sight, does not trouble the makers of globes. They would probably feel there is little that the average person wants to look at beyond 50 degrees latitude - unless of course, you consider that vast ice-covered continent around the South Pole called Antarctica.

But

if the globe-makers did hold such a view (which is unlikely) they would be reckoning

without the scientists who study the marine and land animals, the birds, the

geology, the weather and the plants of such an out of the way place.

But

if the globe-makers did hold such a view (which is unlikely) they would be reckoning

without the scientists who study the marine and land animals, the birds, the

geology, the weather and the plants of such an out of the way place.

It is the plant life on Macquarie Island that concerns us here. Plant scientists from the Australian National Botanic Gardens (ANBG) in Canberra have been on collecting expeditions to Macquarie Island and have brought back some really interesting specimens which they are now cultivating in a quiet corner of the Black Mountain gardens. But before you rush off to look at these amazing plants, let's first consider the island which is their home.

Macquarie Island is 1500km SSE of Tasmania and 1500km north of the Antarctic,

at 54 S 159 E (look 'down under' on your globe). It has what the meteorologists

call a remarkably uniform climate. In fact, it is even said to have one of the

most equable climates on earth.

But

don't be fooled by that word equable. 'Equable' in this case, simply means that

the temperature varies only a few degrees above or below 5 degrees C from day

to day throughout the year. A bit like living permanently in an early morning

Canberra winter.

But

don't be fooled by that word equable. 'Equable' in this case, simply means that

the temperature varies only a few degrees above or below 5 degrees C from day

to day throughout the year. A bit like living permanently in an early morning

Canberra winter.

Precipitation, the condensation in the atmosphere which can be mist, rain, sleet, snow or hail, occurs at Macquarie Island in any one of these forms at any time of the year and often in all forms on the same day. Macquarie Island was discovered in 1810 by Captain Hasselburg on a voyage seeking new sealing grounds.

Tragically, this led to the original populations of fur seal being virtually exterminated within five years of the discovery of the island. The hunters then turned to producing oil from the blubber of southern elephant seals and the fat of penguins.

A few graves, relics and shipwrecks are all that remain from that time of exploitation, the island being declared a sanctuary in 1933. But there was another more serious consequence of their presence on the island. They also left behind additions to the island's original animal and plant life.

The deliberate or accidental introduction of alien animal species such as mice, black rats, cats, wekas (Maori hen) and rabbits, led to the extinction of two endemic birds - a flightless rail and a parakeet. There were possibly three plant species also introduced. But what plants grow on this isolated island so far from the Australian mainland? This has been something that has interested the botanists and horticulturalists at the National Botanic Gardens in Canberra since 1985. It was in that year that the ANBG received some unusual plant material from Geof Copson, a Wildlife Manager with the Tasmanian National Parks and Wildlife Service.

Copson had collected the plants on Macquarie Island and wanted to find out if they could be cultivated successfully in a controlled environment, 'in captivity', so to speak.

The ANBG was very interested. After all, the Canberra Gardens was established for the purpose of growing 'indigenous' Australian flora and Macquarie Island is an Australian territory, administered by the Tasmanian State Government.

But what to do with a collection of subantarctic plants in Canberra, where the winters are cold, but where the summers are dry and often very hot ?

At first, the answer seemed to be to set up the plants in something resembling a fridge - and that is exactly what happened.

Not many of them grew very well, but the exercise was enough to increase the curiosity of the Canberra horticulturalists and botanists.

In 1989 the ANBG decided that its own Director of Botany, Jim Croft, should go to Macquarie Island to collect more plants.

Just before he left, ANBG orchid specialist David Jones had drawn Jim Croft's attention to something of special interest. Jones had seen a fragment of an unusual orchid from the Island. The ANBG had a strong orchid research program under way at the time and Jones believed this particular orchid could turn out to be the southernmost orchid in the world. It was thought to be a Corybas, previously known by the scientific name of C. macranthus, but believed by David Jones to be an undescribed species.

Jim Croft thought the chances of finding the Corybas were slim because the plant is so small, but he was anxious to try to find it growing on the island so it could be described in a scientific way. But the orchid aside, Croft's main job was to collect material which is not commonly seen by the botanical community. The ANBG wanted to make such material easily available for research and for public displays and education.

In the long term there was the possibility that the National Botanic Gardens could start what is called in the scientific world 'ex situ cultivation' of the Macquarie Island plants. In other words, instead of the little 'garden in the fridge' they had started with the early Geof Copson collection, they might start an outdoor subantarctic garden in Canberra.

Jim

Croft's visit to Macquarie Island was made possible with the help of the Australian

National Antarctic Research Expedition (ANARE), which had set up a base on the

island. After many weeks preparation, he set sail for the island on the Polar

Queen, a Norwegian ice-strengthened research vessel chartered by ANARE.

Jim

Croft's visit to Macquarie Island was made possible with the help of the Australian

National Antarctic Research Expedition (ANARE), which had set up a base on the

island. After many weeks preparation, he set sail for the island on the Polar

Queen, a Norwegian ice-strengthened research vessel chartered by ANARE.

He had just five days to make his collections on the island, including a training session with an ANARE team in Tasmania. He was trained in rock climbing and rescue and shipboard safety skills. When he arrived on Macquarie Island, he was pleasantly surprised to find the daytime weather to be not unlike a Canberra winter day, except for one thing - unrelenting wind.

Macquarie island is in the path of winds that have been known since the old sailing ship days as the 'furious fifties'. Jim Croft described the wind on the island as 'uniform in its unpredictability'.

The western side of the island was particularly wild and wind swept. On the leeward side he experienced something new to him - a vertical wind similar to the katabatic, or 'downhill wind' experienced in alpine regions.

The vertical wind was just one of the phenomena that would explain the kind of vegetation he was to find on Macquarie Island. (As we have observed already, it is possible for Macquarie to experience all seasons of the year in just one day). Despite its 'Canberra winter morning' temperature of around five degrees Celsius, the island is probably warmer than its location would indicate.

It is just outside the Antarctic convergence, which is the point where cold sea water from the south meets warm water from the north, bringing a drop in the surface temperature of the ocean.

It is not surprising that Jim Croft found neither trees nor shrubs on Macquarie island. The harsh conditions are not conducive to the growth of trees and shrubs and because there is no tree cover, plants grow in full light.

There are very long daylight hours in summer. With rain on at least 300 days of the year, the daylight, although long, is not strong. In fact, there is only 18 per cent of available solar radiation.

The

tallest plants were grass tussocks of a plant called Poa, or Parodiochloa.

There was a large-leaved plant called Stilbocarpa polaris, known to have

been used by sealers as a vegetable food. There were also sedges, grasses, ferns,

mosses, liverworts and lichens growing in fens, bogs and feldmark.

The

tallest plants were grass tussocks of a plant called Poa, or Parodiochloa.

There was a large-leaved plant called Stilbocarpa polaris, known to have

been used by sealers as a vegetable food. There were also sedges, grasses, ferns,

mosses, liverworts and lichens growing in fens, bogs and feldmark.

Feldmark is a word you won't find in most dictionaries, but it is a word used a lot by botanists to describe the environment in the windswept higher plateau of Macquarie Island. They define it as 'an open subglacial community of dwarf flowering plants, mosses and lichens'.

Although Jim Croft had only five days to make his collections, they were long days and he worked in daylight as late as 10pm. He collected living material, plus samples which would be pressed and dried for the herbarium collection.

The flora on Macquarie Island is not very diverse and there is not a high degree of 'endemism' - that means plants found nowhere else in the world, such as one little cushion-like plant called Azorella and the little Corybas orchid.

All vascular plants on the island (the ones with tissue which transports food and water) are herbs or prostrate sub-shrubs. There are five types of ferns and about 45 different flowering plants including the Corybas .

At

Macquarie Island, Jim Croft found the cryptic Corybas in full flower

growing in wet peat conditions and of course was thrilled to be able to add

it to his collection.

At

Macquarie Island, Jim Croft found the cryptic Corybas in full flower

growing in wet peat conditions and of course was thrilled to be able to add

it to his collection.

After five days of exhausting but satisfying work, he had ten boxes of specimens which were carefully loaded aboard the Polar Queen for the first stage of their journey to the National Botanic Gardens. The boxes of specimens, on reaching mainland Australia, needed to be cleared by the Australian Quarantine Inspection Service (AQIS), whose job it is to minimise the risk of introducing diseases in either plants or soil. To meet these requirements Croft had to wash the soil from the roots of the plants and pack the samples in sphagnum and vermiculite potting medium to keep them alive.

Once at the ANBG nursery, staff went to work propagating the collection in a cool room lit by fluorescent lights and with an evaporative air conditioner Jim Croft had brought from home. Some of the plants were sent across Clunies Ross Street to the Australian National University, which had more sophisticated growth cabinets with light and temperature adjusted to better reproduce the Macquarie Island environment.

But

the environment that both the Botanic Gardens and the ANU created lacked one

important ingredient.

But

the environment that both the Botanic Gardens and the ANU created lacked one

important ingredient.

It was that wind again!

The constant Macquarie Island westerly wind - the vertical wind that blew 'down hill' on Jim Croft during his visit - could not be reproduced 'in captivity'. Some of the captive plants were actually enjoying the change. They grew too fast and 'burned themselves out'. But the losses were small and the collection was soon attracting wider interest.

The Visitor Centre at the Gardens set up a delicatessen refrigerator, put in some soil and held a 'life in the fridge' display with much success.

One disappointment was the shy little Corybas orchid. It would not grow, although its failure may have been due to over watering, a common human error when growing plants indoors. Another frustration was the spectacular, large leafed, daisy-like Pleurophyllum hookeri. Jim Croft thought it had possibilities as a rockery plant if it could be grown commercially. Despite being equipped with a large root, almost like a carrot, the trauma of being uprooted from its island was too much and it died.

This was puzzling to Jim Croft, because on the island the plant had been growing in dry sand or in very poor clay. But its failure may have been linked to a phenomenon called mycorrhizal fungal activity. (In the plant world, there is a class of fungi that has a symbiotic relationship with the roots of plants. The fungi enable the plants to access the minimal nutrients in poor soil. In return, the fungi live on the plant's roots and obtain carbon based nutrients. The most famous mycorrhizal fungus is the truffle.)

The orchid had escaped them and so had the carrot-rooted Pleurophyllum hookeri.

It was clear to the ANBG scientists that more material was needed from the island and more work needed to be done.

Article By Jan Smith

Read about the second expedition to Macquarie Island and another Australian subantarctic territory - Heard Island in the next article in this series.