Mistletoe in folk legend and medicine

The traditional mistletoe of Europe and Asia, Viscum album

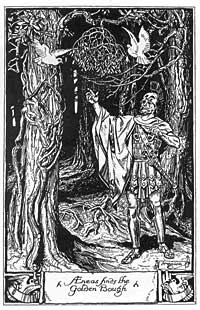

The traditional mistletoe of Europe and Asia, Viscum album ![]() , features prominently in ancient legend and in mythology. For example, the Golden Bough was probably mistletoe. The Golden Bough was carried by Aeneas, who had earlier escaped from Troy when it was destroyed by the Greeks. He had many adventures, and was persecuted by some gods and protected by others. Aeneas descended into Hades to consult his dead father, Anchises, but only after he had plucked the Golden Bough, at Sybil’s direction, to carry with him on his perilous journey.

, features prominently in ancient legend and in mythology. For example, the Golden Bough was probably mistletoe. The Golden Bough was carried by Aeneas, who had earlier escaped from Troy when it was destroyed by the Greeks. He had many adventures, and was persecuted by some gods and protected by others. Aeneas descended into Hades to consult his dead father, Anchises, but only after he had plucked the Golden Bough, at Sybil’s direction, to carry with him on his perilous journey.

|

The Golden Bough is also identified with the sacred branches which grew in the sanctuary of Diana at Nemi, the sanctuary being a grove of oak trees. To become High Priest of the sanctuary, one had first to succeed in plucking the sacred bough, and then in killing the reigning priest.

Superstitions about mistletoe are widespread in many cultures in different parts of the world, and therefore involve numerous mistletoe species other than V. album. Even in this wider context mistletoe is more often a good omen than a bad one. Uses for mistletoe, which often involved special recipes and complicated rituals, include gaining protection from fires, keeping witches away, as a divining rod to find hidden treasure, keeping horses from straying, promoting fertility in domestic herds and crops, giving strength to wrestlers, success to hunters, avoiding military service, protecting from wounds in battle, forcing evil spirits from hiding and making them tell the truth, preventing nightmares, providing refuge for woodland spirits in winter, and keeping witches from meat in the smokehouse.

Mistletoe was used medicinally either by placing it on the affected part or by drinking a decoction of the plant. At various times in various parts of the world it has been used to treat epilepsy, the bites of mad dogs and wild animals, strained muscles, toothache, sores, itch, weakness of vision, impetigo, dandruff, regeneration of lost fingernails, common cold, ulcers, poisoning, promotion of muscular relaxation before childbirth, to hasten menstruation, treat warts, snakebite, fever, syphilis, beri-beri, ringworm, headaches, gout and worms. In England, if a child had intestinal worms, he/she was given bark of mistletoe taken from an oak tree, powdered in warm milk, and the worms would supposedly die exactly nine hours later.

In the matter of human fertility, early peasants in England and continental Europe and also the Ainu people of Japan regarded mistletoe as a symbol of fertility. Mistletoe was eaten by barren women. It was carried about by women of ancient Rome for the same reason. Austrian couples were helped to parenthood by a piece of mistletoe hidden secretly in the bedroom. A German recipe to induce pregnancy was as follows: three mistletoe twigs should be boiled for three minutes in 1.5 litres of water, accompanied by the invocation of the three holy names, and both spouses should drink the concoction eight days before the onset of the wife’s menstrual period.

In Australia the indigenous people certainly recognized mistletoes and had specific names for them. It seems, however, that mistletoes have little place in cultural beliefs. It has been reported that some Torres Strait Islanders believe that a pregnant woman who touches mistletoe will have twins.

As one might expect, there was much ceremony attached to collecting mistletoe. In England and elsewhere in Europe mistletoe was only esteemed when found growing on oak trees. In Japan the Ainu people favoured only the mistletoe which grew on the sacred willow tree. Several cultural groups, including the Romans and some present-day people, believed that mistletoe was only effective if it was not allowed to touch the ground. The Swiss shot the mistletoe down from oak trees with bow and arrow; the moon had to be on the wane, the sun in the sign of Sagittarius, and the mistletoe twigs had to be caught in the left hand. In other cases, however, mistletoe must not be touched by hand while being collected. In Sweden mistletoe had to grow on oak, and had to be knocked down with stones. The Druids gathered mistletoe on the sixth day of the moon at the end of the year, with very solemn rites. Two white bulls were led by a priest, also clothed in white, to an oak tree bearing mistletoe. The priest silently climbed the tree and carefully cut the mistletoe with a golden sickle. The pieces were caught in a white mantle. The bulls were slain as sacrifices, and prayers were offered for the wellbeing of all involved. The pieces of mistletoe were then distributed and worn as rings and bracelets.

The reason for the importance of mistletoe in legend and medicine probably relates to the growth habit of the plant. Being a parasite, and therefore appearing as a distinct clump of foliage on a tree, it would have attracted the attention of primitive people. Because mistletoe is evergreen, it would have been even more conspicuous when observed in winter on a deciduous host tree. Furthermore it would have had special significance when the host tree itself was sacred.

It was widely believed, then, that the evergreen mistletoe kept the deciduous sacred host tree alive during winter while it was leafless. The mistletoe was regarded as the heart or the life of the god of the sacred tree. Balder was in fact a personification of the oak tree, and his life was guarded in the mistletoe which grew on the oak. The Druids in Gaul esteemed nothing more sacred than the oak and the mistletoe which grew on it, and the Ainu people of Japan had similar beliefs with regard to their sacred willow.

It is noteworthy that the medicinal properties of mistletoe may not be due entirely to superstitious beliefs. In the twentieth century mistletoe became an accepted pharmaceutical plant. Extracts from V. album have been reported to have the properties of reducing blood pressure, increasing urine production, toning cardiac muscle, checking haemorrhages, and acting as an antispasmodic (cf. its ancient use as a treatment for epilepsy).

![An Australian Government Initiative [logo]](/images/austgovt_brown_90px.gif)