Lichen biogeography

Before getting to the question of 'What is biogeography?' I'll say something about the lichen featured in the illustration at the top of this page, since it will provide a simple introduction to some biogeographical issues. The illustration, by James Sowerby, is part of plate 2548 in JE Smith's English Botany. That plate is captioned Lichen leucomelos, dated May 1 1813 and Smith's accompanying text begins with these words:

Discovered by Mr. W.J. Hooker at Babbicombe in Devonshire last February. The species had never before been met with in Britain, but it is a native of the West Indies and of St. Helena.

Babbicombe was a village on the south Devon coast, near Torquay, and now (as Babbacombe) is part of an expanded Torquay. Taken at face value the above extract suggests that Lichen leucomelos may have been introduced into England. Additional support for that idea comes from the fact that the first published description, by Linnaeus, had appeared in 1763 and he had noted only "America meridionalis" as a location. If the species had been introduced into England, how had it arrived there? St. Helena in the South Atlantic was a British possession, visited by ships travelling between England and Asia, with many vessels stopping for extended periods for refitting or revictualling. Similarly there was much ship movement between England and the British possessions in the West Indies. Given that both locations were on well-travelled routes a plausible hypothesis would be that the lichen was brought to England, perhaps inadvertently, by one or more merchant or naval ships. After all, there are many well-known cases of organisms dispersed by humans, either deliberately or inadvertently - rabbits and rats, to give just two examples.

Why was Lichen leucomelos found in Devon and not recorded elsewhere in England? Had it been off-loaded in Plymouth, a major seaport about 50 kilometres west of Torquay? That could explain the finding of the species in Devon and it would also have been a fortuitous entry port. Chapter 1 of Thomas Shapter's The climate of the south of Devon, and its influence upon health (published in 1842) begins with the words:

Devonshire has long been celebrated for the mildness of its seasons, and on this account has been a favourite resort of the invalid, and generally attractive as a residence...

and the second page includes the observation that the

...more striking characteristic of the climate of Devon generally, is that of being warm and moist...

Both the West Indies and the island of St. Helena have tropical climates. If the lichen had arrived through Plymouth it would have entered an area of England with a milder climate, with conditions closest to those of the lichen's tropical homes. On the other hand, perhaps the lichen had entered through other ports, and so found its way to several places in England apart from Devon, but been able to survive only in Devon's milder climate. The lichen appeared to be fairly well established in Devon since Smith wrote that the "fronds grow in dense, lax tufts, spreading amongst thyme, & in heathy places" and he noted the striking "coal-black, simple or branched marginal hairs" that grew off the "fronds" that constituted the lichen thallus. The image on the right, also from Sowerby's plate, shows the marginal cilia on one of the otherwise whitish thallus lobes (or "fronds", to use Smith's word).

Both the West Indies and the island of St. Helena have tropical climates. If the lichen had arrived through Plymouth it would have entered an area of England with a milder climate, with conditions closest to those of the lichen's tropical homes. On the other hand, perhaps the lichen had entered through other ports, and so found its way to several places in England apart from Devon, but been able to survive only in Devon's milder climate. The lichen appeared to be fairly well established in Devon since Smith wrote that the "fronds grow in dense, lax tufts, spreading amongst thyme, & in heathy places" and he noted the striking "coal-black, simple or branched marginal hairs" that grew off the "fronds" that constituted the lichen thallus. The image on the right, also from Sowerby's plate, shows the marginal cilia on one of the otherwise whitish thallus lobes (or "fronds", to use Smith's word).

St. Helena is several thousand kilometres distant from the West Indies and so the extract that started all these musings also prompts the question: Where else is the species found? Does it occur on the African mainland or in areas of South America between St. Helena and the West Indies? If it had been introduced to England, had it also been introduced to other warm parts of Europe?

What is biogeography?

I don't know whether the hypotheses given above are true but, as said earlier, they and the related questions serve as an introduction to biogeographical issues. Biogeography is the study of both the current distribution of living organisms and the reasons for those distributions. Ideally it would be possible to devise a well-supported hypothesis to explain any given distribution but that's not always possible. In the various biogeography pages you will see some hypotheses but more often you will see descriptions of various distributions. When it comes to known distributions, at one extreme are those species that are known to be very widespread and at the other are those so far known from only a very limited area. Here are some examples:

Psora decipiens

is known from Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe and North and South America.

Neophyllis melacarpa

is known from eastern Australia and New Zealand

Xanthoparmelia ewersii

is thus far known only from South Australia.

For the most part the biogeography pages on this website are devoted to a discussion of LICHENS IN AUSTRALIA but on the LICHEN DISTRIBUTIONS page you will find brief descriptions of the various distribution patterns of the world's lichens.

Distribution patterns are the starting point for any biogeographical investigation and sometimes they will raise questions immediately. You've seen that with Lichen leucomelos. Given that St. Helena and the West Indies are so far apart it's natural to wonder if the species also occurs in the area in between. Of course if, after much searching, the species were found nowhere else you'd be left with the puzzle of why the species was found only in those two areas. However, just staring at a puzzling distribution map will produce no plausible explanations. For that you need to bring in other evidence. Current distributions (of plants, animals, lichens, etc.) are the result of the interplay of numerous factors which have acted over past centuries, millennia or eons and continue to act today. A few such factors are the movement of continents, climate, wind patterns and international commerce. For example, you've just seen the suggestion that humans may have been responsible for transporting Lichen leucomelos to England by ship and that hypothesis relied on non-botanical information, namely knowledge of the history of British involvement with the West Indies and St. Helena.

Thus far the focus has been on species and you've seen that some species are widespread while others have a very restricted distribution. You could also look at the genus level and you'd find that some genera are very widespread while others are much more restricted. Note that while a genus may be widespread, not all the species in the genus need be. For example the genus Xanthoparmelia is found worldwide but the species Xanthoparmelia ewersii is known only from South Australia and it can be instructive to look at BIOGEOGRAPHY AT DIFFERENT LEVELS.

Biogeography - always a work in progress

Going back to the Lichen leucomelos example, you've seen how even the very limited evidence presented in English Botany, when combined with knowledge about ship routes and climate, has generated several ideas. That example, though very simple, already gives you an inkling of how distributional information can be linked with other factors to generate hypotheses to account for those distributions - or suggestions as to where else to look for a species. Of course, any hypothesis is only as good as the evidence that supports it and a hypothesis is always subject to change. Before you undertake any detailed biogeographical analysis, you need comprehensive and accurate knowledge of the species that occur in different areas of the world. Clearly such knowledge is fundamental, yet it is far from complete since many areas of the world are still largely unexplored from a lichen point of view. Not surprisingly, discoveries in such areas may dramatically alter thoughts about the origin, evolution or migration of lichen species and biogeography is therefore always a work-in-progress. Thus you should always view biogeographical hypotheses with a healthy scepticism and bear in mind the evidence or assumptions on which any biogeographical hypothesis is based. The FUSCOPANNARIA SUBIMMIXTA STORY gives an example of a species with a changing biogeographic story.

Even when areas have been lichenologically explored to a good degree, there is still the question of the accuracy of the names applied. If you look at the HISTORY OF AUSTRALIAN LICHENOLOGY you'll see that until the late 1800s there were no resident Australian lichenologists, though before then numerous specimens had been collected and shipped to Europe for study. This led to many Australian specimens being given European species names during the 1800s and early 1900s. Such identifications were based largely on macroscopic similarities. Certainly there are many species common to Australia and Europe but re-examination of numerous old collections has also shown that many European species, once thought to occur in Australia, do not in fact occur here. Such re-examinations have benefited from the development of tools such as high quality light and electron microscopes, improved techniques of chemical analysis and, most recently, DNA analysis. It has also been the case that new species have been described from Australian specimens, where later study has in fact shown such species to be the same as previously known overseas species. There are still species recorded for Australia, but with those records based on old identifications with no recent re-examination of the actual specimens. The records may be correct but, pending the necessary re-examination, should be treated as "not proven". You therefore need to be careful before using old literature to support any statements about the relationships between the lichens of Australia and those of the rest of the world.

Finally, lichenologists are human and do at times make errors that have biogeographical consequences. Apart from mistakes in identification, errors in geography may also happen. Several print and online editions of the Australian lichen checklist, at least as late as 2006, had recorded Laurera cumingii as occurring in Australia but a study published in 2009 found no evidence of the species' occurrence in Australia. The erroneous claim appears to have originated in a 1957 paper, by a French lichenologist, who mistakenly regarded New Zealand as a region of Australia![]() .

.

In the early 1800s Robert Brown collected a number of lichens from south-eastern Australia but it was not until 1880, long after Brown's death, that a paper about these collections appeared. The author was the British lichenologist James Crombie and his paper included misleading geographical information. According to the paper Brown had collected Xanthoparmelia australiensis and Xanthoparmelia semiviridis from Tasmania - but both species are known only from the generally drier areas of mainland Australia. It's very likely that Brown had collected them in South Australia but sometime between collection and publication there was a mix-up.

Taxonomic changes and biogeography

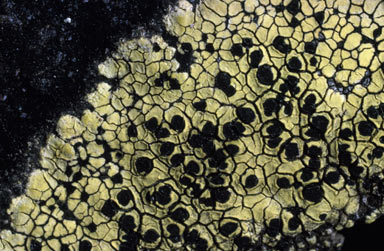

It is clear that taxonomic changes may lead to changes in biogeographic thinking. Suppose that species A (endemic in Australia) and species B (endemic in Japan), though similar, have been thought to be distinct, but that new research gives compelling evidence that the two are in fact identical. One immediate consequence of such a finding would be the reduction by one of the endemic species counts in both Australia and Japan. Before the new findings one might have hypothesized that in the distant past there had been an ancestral species (call it C) that by some mutations had given rise to A and B. With the new findings there's no need for the ancestor C, but there is now the challenge of explaining the occurrence of this species in just Australia and Japan - or would more careful searching find the species elsewhere as well? The reverse also happens - what had been thought to be a single species (perhaps widespread) is shown to be a complex of closely related species. If the 'original' species had been widespread the biogeographic issue changes from proposing a reason for wide distribution of a single species to looking at the evolutionary relationships between the new species that result from the splitting of the original species. Many books or websites talk of Rhizocarpon geographicum as being a cosmopolitan species and this website is no different. However some lichenologists think there is evidence to support the idea that rather than being one cosmopolitan species, 'Rhizocarpon geographicum' is in fact a group of superficially similar, but subtly different, species.

Rhizocarpon geographicum - showing apothecia |

What of Lichen leucomelos today?

The first thing to note is that the genus name Lichen was used by Linnaeus but it became clear that in that one genus Linnaeus had grouped a heterogeneous mix of organisms which warranted a number of distinct generic names. Today Lichen leucomelos is known as Heterodermia leucomela. Smith's English Botany gave very limited geographic information about this species but fieldwork through the 1800s and 1900s has shown it to be widespread and common in the tropical to sub-tropical areas of the world and in Australia it is known from Queensland. Amongst the features that help identify the species is the thallus composed of whitish strap-like lobes, each of which carries numerous black, hair-like cilia on the margins. You saw those in one of the Sowerby illustrations earlier on this page and you can see those whitish lobes and dark cilia in this photograph ![]() , of a herbarium specimen collected in Queensland. In a paper published in 1976 two lichenologists separated the species into two subspecies: Heterodermia leucomela subspecies leucomela and Heterodermia leucomela subspecies boryi. The latter differs from the former in several anatomical features and also chemically, in that it lacks depsidones. Both subspecies are widespread in the tropics and, according to those two lichenologists, the depsidone-containing subspecies extends into the cooler, temperate areas. Various post-1976 publications don't distinguish the subspecies so you will see temperate records of Heterodermia leucomela, without reference to a subspecies

, of a herbarium specimen collected in Queensland. In a paper published in 1976 two lichenologists separated the species into two subspecies: Heterodermia leucomela subspecies leucomela and Heterodermia leucomela subspecies boryi. The latter differs from the former in several anatomical features and also chemically, in that it lacks depsidones. Both subspecies are widespread in the tropics and, according to those two lichenologists, the depsidone-containing subspecies extends into the cooler, temperate areas. Various post-1976 publications don't distinguish the subspecies so you will see temperate records of Heterodermia leucomela, without reference to a subspecies![]() .

.

What of the hypothesis of Heterodermia leucomela having been introduced to England, perhaps by ship? The species is certainly far commoner in the tropics and sub-tropics, suggesting it has dispersed from there to temperate areas both north and south of the equator. For example it is found in the North and South Islands of New Zealand. However I know of no study of the possible dispersal of this species![]() .

.

There's more...

...about Australian lichen biogeography on the LICHENS IN AUSTRALIA pages.

Lichen biogeography pages on this website Distribution patterns |

![An Australian Government Initiative [logo]](/images/austgovt_brown_90px.gif)